|

M

Life in Japan amid the corona virus

If someone asked me what it is like living in Japan while the coronavirus is threatening the country (and the world), I would probably say “I have nothing to compare it to”, as I have obviously not been to any other country since the pandemic hit. However, as a foreign resident of Japan, my experiences may be different enough to be interesting.

I have been in Japan for quite a long time, so I am fortunate enough to generally understand what is going on. However, for someone new to Japan, or someone who does not speak or read Japanese well, it could be a very different experience. While there is information available in multiple languages, it may not always be accurate, or properly translated, and if there is no such information in your own language, it may be stressful if you do not understand.

Fortunately, thanks to the internet and media, the basic methods to counter and prevent the coronavirus are both simple and widely known: social distancing, hand washing, the use of masks, and avoiding crowded places as much as possible. These themes seem to be accepted almost everywhere across the globe. They can also be described in pictures, thus making words unnecessary, or at least less necessary. Japan is often considered a country with high overall standards of cleanliness, which is a major factor in preventing the spread of illness. (It is common to hear visitors to Japan talk about how well maintained the toilets and bathrooms are in stations, shops, etc). So this should, in theory, be one way of fighting the coronavirus.

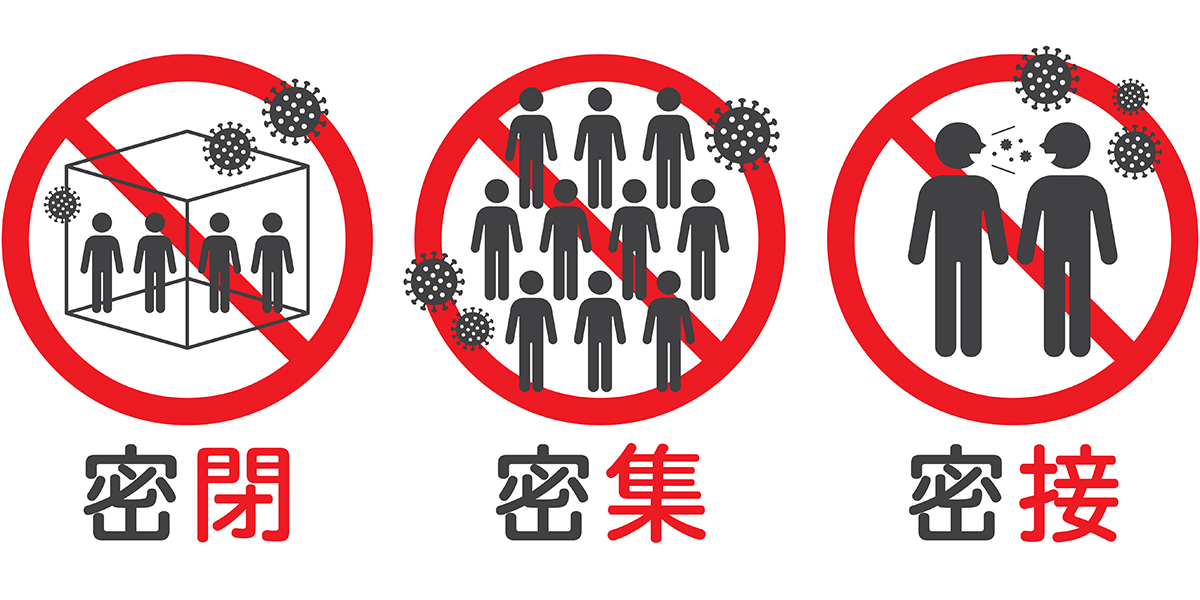

Japan has its own set of rules as well: the three “mitsu”s. These are three phrases which all start with the character 密, (“mitsu”, or “density”). They are:

密閉 (“mippei”, meaning “airtight” and referring to the need for a sufficient level of ventilation)

密集 (“misshu”, meaning “crowded” and referring to places where people gather in large numbers)

密接 (“missetsu”, meaning “intimate” and referring to the physical distance between people; this is probably Japan’s equivalent of “social distancing”. Interestingly, “social distancing” - in English - is seen frequently here, for instance on park benches, in restaurants, etc).

Personal impressions:

As a rule, I have found that the Japanese people are very good when it comes to co-operating to prevent the spread of the virus. Walking around town, I would guess that up to 90 per cent of people wear masks, which is an impressive figure. However, it can depend on the area; in my experience the more urban and central the area is, the more masks you see. For instance, in places like the areas around major stations and commercial (shopping) areas, almost everyone has a mask on. This is a good sign, as these places can get very, very crowded. If you go further out into the suburbs, you will certainly notice more people without a mask, but compliance is still high.

It is not unusual to wear a mask in Japan anyway; people do so when they have a cold, or when hay fever / allergy season comes along. So wearing a mask in Japan does not feel strange, even for people who come from countries where masks are not commonly seen. In fact, at the moment it is people not wearing masks who stand out. This also explains the long queues at pharmacies when the coronavirus started really becoming big news; masks (and toilet paper) were very hard to get hold of, and many places which sold them would limit them to one pack per customer. We joke that while the British (of which I am one) like standing in queues, the Japanese are world champions at it.

If there is one place you would want people to wear masks, it is on Japan’s famously crowded subway trains. Fortunately, almost everyone does. I said that “up to 90 percent” of people wore masks outside, but on the trains it is even higher than that. Furthermore, there is not much talking going on as everyone is either looking out of the window or surfing the internet on their smartphone. During the “state of emergency” announced by the Japanese government, stations and trains were far less crowded than usual, but they are getting back to their normal state, so it is reassuring to see masks everywhere when you get on a train.

The picture below is of a platform at Shinjuku station, which is officially – by number of users – the busiest station in the entire world. To see it this empty is very nearly a once-in-a-lifetime event.

There is a very interesting point to note about Japan and the coronavirus: it is technically impossible to have a real “lockdown” in Japan. The government does not have the authority to make people stay inside. The Japanese constitution gives citizens freedom of movement (in Japanese, 移動の自由), so the government can declare (and has declared) a state of emergency and can ask or strongly request people to stay at home, but cannot force them to. They rely instead on the people co-operating. I can’t imagine this system working in many countries, but in Japan it seems to be relatively effective.

During the state of emergency, many shops remained closed or shortened their opening hours. Now that the state of emergency has been lifted – for the time being, at least – things are somewhat more normal. However, many shops now provide hand sanitizer at the entrance, almost all shops have a sign requesting customers to wear a mask, and some will ask to take your temperature before allowing you inside. Again, the Japanese tendency to co-operate means that this is possible. I have also seen “no mask means no service” signs here (normally, the signs ask customers to wear a mask, but don’t always go as far as “no mask, no service”). This was a little surprising, as so many people wear masks anyway, I would think a sign like this would not be necessary.

While Japan is often thought of as a very high-tech country (which is true in some ways, but not in others), sometimes they come up with very simple, low-tech, solutions to problems. Currently, convenience stores and other shops feature plastic partitions between customers and staff. Simple, but presumably effective.

Even though the people of Japan are generally very good at co-operating during a difficult situation or a disaster (other examples would be earthquakes, typhoons, etc.), the country has nonetheless recently seen a notable increase in cases. While the numbers are not as bad as what many other countries have experienced, it is still a definite increase, and there is discussion of another possible state of emergency – in fact, Okinawa has recently declared its own. I hope that if the government does indeed declare a second state of emergency, people will comply as they did the first time around.

I am originally from the UK, and while I have obviously not been there during the coronavirus pandemic, the general opinion is that the government did not handle it well at all (which is reflected in the relatively high number of cases and deaths). While the Prime Minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, has seen a somewhat negative reaction towards his government’s overall approach, the Mayor of Tokyo, Yuriko Koike, earned respect for demonstrating leadership (and this certainly helped her win re-election very easily). At the very least, the government seems to be working with scientists and experts, which is what you would hope they would do.

I remember reading a book about Japan which said that the influence of Buddhism gave the Japanese a certain attitude towards disaster and misfortune, which is demonstrated by the Japanese saying しょうがない, usually translated as something like “there is nothing that can be done about it”. However, their ability to co-operate in such times suggests that they do think something can be done about it. This contradiction is one of the most interesting things about being in Japan.

The coronavirus is a worldwide issue, but the country you are in (whether it is your country of birth or not) will of course influence how you see things. Overall, I would say that Japan’s handling of the coronavirus would be best described as “better than some, worse than others”, and that the main reason why cases are still comparatively low (given the population) is not the political response, but the actions of the people. However, it looks like a long road ahead for all countries. I hope the tendency of many Japanese people to listen to and follow requests, and to consider their town / prefecture / country as well as themselves, will help the country get through this pandemic.

Click here to get the latest information on Central Japan.Centrip Japan - Nagoya and Chubu Information