|

Centrip Editorial Board

Nakasendo: Walk along the Snowy Yogawa-michi Walking Trail

Two main highways connecting Edo (Tokyo) and Kyoto during the Edo period (1603-1868), the route along the sea was called the Tokaido, and the inland mountainous route was called the Nakasendo. The Tokaido highway had 53 inns and was 514km long, and the Nakasendo had 69 inns and was 534km long. The number of feudal lords that used the Nakasendo to travel to and from Edo was a quarter of the total number that used the Tokaido. However, unlike the Tokaido, which was often flooded by rising water, the Nakasendo was almost free of water-related delays, making it easier to plan an itinerary. It was important in various historical instances, such as when princesses from Kyoto would go to Edo to marry into the Shogun's family.

The Tokaido saw rapid modernization and development after the Meiji Restoration, while the Nakasendo, which runs through mountainous terrain, developed slower. As a result, the old towns and roads still retain much of their original atmosphere. Currently, walks that take visitors through the inn towns along the Nakasendo, especially the deep mountain area called Kisoji, are gaining popularity.

While the best-known route on the Nakasendo walk is the Magome Pass between Magomejuku and Tsumagojuku, we decided to walk the Yogawa-michi Walking Trail. This route does not have the glamour of tourist attractions, but it gives you a deep sense of the atmosphere of the old Nakasendo and its Japanese character.

The Yogawamichi Walking Trail is a bypass and not the main road on the Nakasendo. It is a mountain trail built as a detour if there was a flood or landslide on the Kiso River. It corresponds to the former post towns, Midono-no-juku and Nojiri-juku on the Nakasendo. In today's terms, it covers the railway section between Nagiso Station and Nojiri Station, the distance of about two stations, on the JR Chuo Line.

Today, I visited the Yogawa-michi Walking Trail as part of a day trip from Nagoya.

The first Wide View Shinano train departs Nagoya Station at 7:00 am, arriving at Nagiso Station one hour later. This area has a long history as a major production center for Japan's forestry industry. You'll see evidence of this from the piles of Japanese cypress at the platform of Nagiso Station.

As soon as I started walking from Nagiso Station, I saw an information board for Momosuke-bashi Bridge.

Momosuke-bashi Bridge was instrumental in the development of hydroelectric power generation on the Kiso River. Momosuke Fukuzawa was a key figure in the development of hydroelectric power generation on the Kiso River. He built the 247-meter-long, 2.7-meter-wide suspension bridge with distinctive wooden bridge girders in the 1920s for transporting materials to construct the Yomikaki Power Station.

During this period, Japan underwent rapid modernization. Modernization created an urgent need to shift from small-scale coal-fired power generation to high-capacity, low-cost hydroelectric power generation. The Kiso River attracted attention for developing hydroelectric power generation because of the large volume of water rapid current. Momosuke Fukuzawa built seven power plants in the Kiso River basin between 1919 and 1926 and became known as "The King of Electrical Power." The swiftness of the Kiso River is viewable from the riverbank; as it flows over the various levels constructed to prevent flooding.

The area around Nagiso Station was once known as Midono-juku, but now there is little trace of the old post town, only a sign and some slight remains of the main camp are left.

Since the Yogawa-michi Walking Trail passes through narrow streets between the houses, you may be confused about which direction to follow. However, many signposts point to the Nakasendo as you follow the road to Nojiri Station. After a short walk, the terraced rice paddies, a characteristic of mountainous areas, appear.

As I walked along a small path among well-maintained cypress trees, I saw small historical sites, such as the Nijusanyato, a memorial to old folk traditions for praying for a good harvest.

At the end of the road, the guesthouse Yui-an stands on its own.

This facility is a renovated old private house. Upon entering, the thick beams used in construction are impressive, and a sunken hearth is here for guests to gather around, with a fully equipped kitchen space. This guesthouse is a great location to serve as a base for enjoyable strolls along the Nakasendo.

Nagiso combines the Chinese characters for "Na (South)" and "Kiso." It is in the warmer and not as snowy southern area of the mountainous Kiso region. But, like today, and at the end of the year, much of the route gets covered in snow.

I followed my guide, Mr. Koshi of the Kiso Ontake Tourist Bureau, and walked along snowy the Autumn Ontake Old Road. There were almost no steep paths, and the walk was comfortable, and the sunlight glittering off the snow was dazzling.

Along the route is a hand-made gate that prevents wild animals from destroying the rice fields. The sign on the gate says "Push" in English and Japanese, so don't hesitate to proceed.

Beyond the gate are rice fields with steps that take advantage of the slopes in this mountainous area. At the end of the fields is the Yogawa village headman's house, and the Yogawa-michi Walking Trail continues between the houses.

After I greeted the goats, I continued along the gentle farm road and reached a covered rest area before turning back to the mountain road.

In the past, processions of princesses that took the Nakasendo may have rested in this area. It took us about three hours to reach here from Nagiso Station, taking pictures along the way, so high time for a break. There are no stores in the area, so pack a lunch to keep up your energy.

During the heyday of the forestry industry, the Kiso Forest Railway transported lumber cut in the mountains.

Industry decline forced abandonment of the railroad, but remains of the railroad are seen in many places while walking along the Yogawa-michi Walking Trail.

As I walked along, I noticed that the roots of cypress trees are exposed here and there along the forest path. Root exposure occurs because the rocky terrain stops the roots from reaching deep underground.

The Kiso area receives a lot of rainfall, and in the winter is surrounded by snow and severely cold. The Japanese cypress growing in this harsh natural environment takes longer to mature than cypress grew elsewhere in Japan. This aging process creates beautiful rings on the cross-section of the tree, and the wood is considered high-grade and is a staple of Japanese architecture since ancient times.

Suddenly, the cypress path ended, and I emerged in an open area. Beyond the trail led to a smaller path through a bamboo grove.

After passing through the bamboo grove, I descend an abrupt slope. The stairs are steel and steep, so take care on your way down.

After some time, I arrived at Amida Hall. I don't know the details of the temple, but it must have watched over travelers on the Yogawa-michi Walking Trail in times long past.

At various points along the way, I could see the peaks of the Japanese Alps. The snow-capped mountains are beautiful juxtaposed against the blue sky.

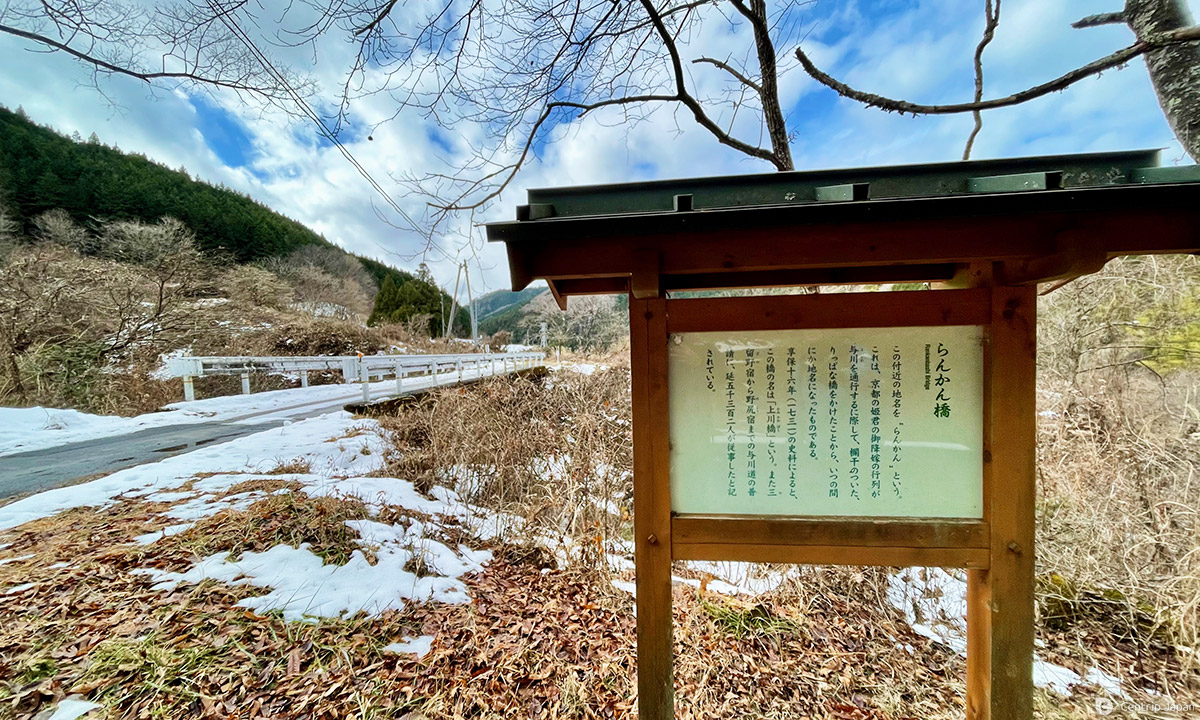

Eventually, I arrived at the Rankan Bridge. In the past, when the princess's procession had to pass this river, they put workers to task building a magnificent bridge with ornate railings and parapets. Unfortunately, there is no trace of it now, only a tasteless concrete bridge. After passing this bridge, we were almost at the highest point of the Yogawa-michi Walking Trail, the Nenouetoge Pass.

Before the pass, the road gets a little steeper.

The bell is there to scare off bears. There aren't many encounters in this area, but the bell remains as a precaution. Ringing the bell is recommended so you don't startle any bears that may be hibernating.

The power of the cypress trees rising straight up is impressive. I came upon a bridge over a stream and saw a small stone statue at its end.

The stone is an 18th-century Buddhist road marker inscribed with the words "Right Yamamichi, Left Nojiri Michi." This marker remains from ancient times when the Yogawa-michi Walking Trail was a detour for the Nakasendo. I took the left trail to Yamamichi.

Climbing up the last steep slope, I reached the highest point of Nenouetoge Pass. I started at Nagiso Station a little after 8:00 am and reached the highest point at 12:20 pm.

From Nenouetoge Pass, it's just a matter of heading down the road.

From the Pass, the trail was somewhat monotonous, but after an hour's walk, I arrived at Nojiri-juku.

Nojiri-juku, once a bustling inn town, lost much of its character to a fire in the 1930s. However, if you look closely, the remains of the old post town are seen in winding roads called Masugata, designed to keep out enemies.

Nojiri Station is unstaffed and stands quietly in the middle of Nojiri Inn. I arrived at the station a little after 2:00 pm and began my journey home.

The route I took was about 10 km long, with an altitude difference of about 450 meters, from the starting point. Nagiso Station is about 400 meters above sea level, and Nenouetoge Pass is about 850 meters above sea level. It took me about five to six hours of leisurely walking with breaks in between.

The scenery looked like the Edo period, as though time had stopped. The upright cypress trees reaching for the sky and snow-capped mountains create a wonderful experience. This trail is still an undiscovered tourist route, and I spent the day in quiet solitude without encountering any other travelers. If you are looking to get away from congested areas that are dangerous during the COVID-19 crisis, a walk along the Yogawa-michi Walking Trail might be just what you need.

Click here to get the latest information on Central Japan.Centrip Japan - Nagoya and Chubu Information